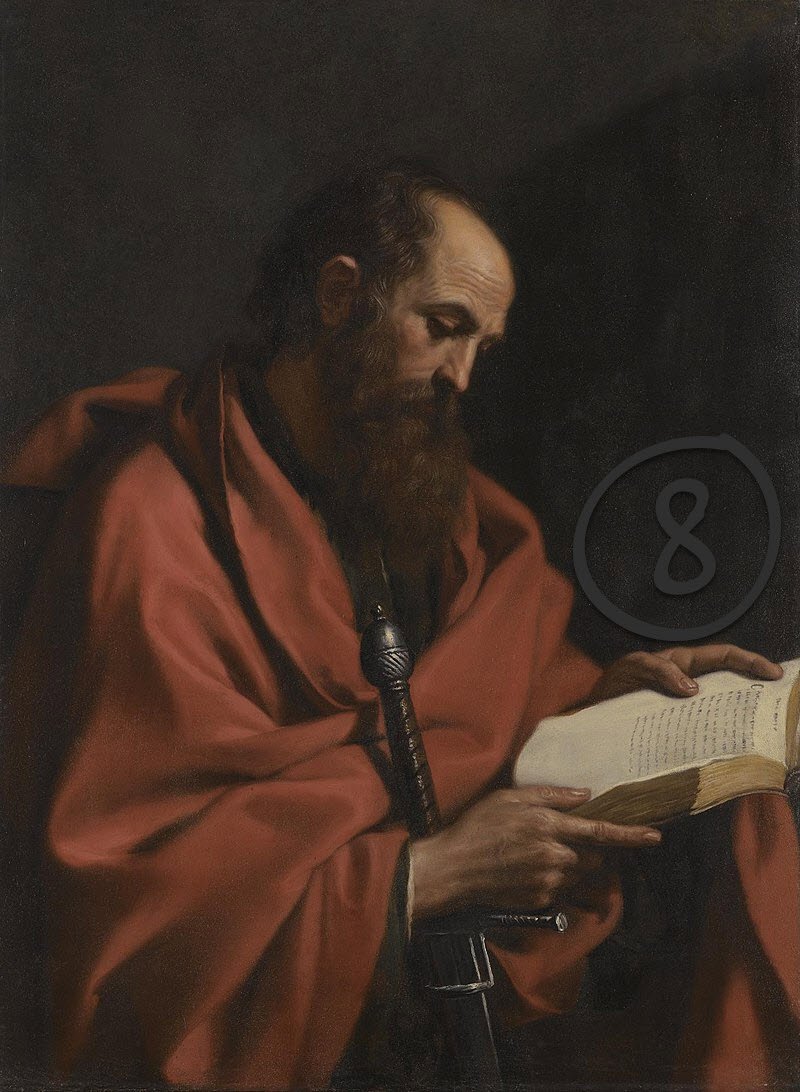

All Paul Fall #8: Philemon

This is Part 8 of a 13-part series of brief reflections on the letters of Paul. These reflections are part of the Saturday Morning Prayer service for St. Stephen’s Episcopal Cathedral’s Facebook Live Ministry.

Philemon, I thank my God every time I mention you in my prayers because I’ve heard of your love and faithfulness, which you have both for the Lord Jesus and for all God’s people.

Philemon 4-5, 8-16 (Common English Bible)

Therefore, though I have enough confidence in Christ to command you to do the right thing, I would rather appeal to you through love. I, Paul—an old man, and now also a prisoner for Christ Jesus— appeal to you for my child Onesimus. I became his father in the faith during my time in prison. He was useless to you before, but now he is useful to both of us. I’m sending him back to you, which is like sending you my own heart. I considered keeping him with me so that he might serve me in your place during my time in prison because of the gospel. However, I didn’t want to do anything without your consent so that your act of kindness would occur willingly and not under pressure. Maybe this is the reason that Onesimus was separated from you for a while so that you might have him back forever— no longer as a slave but more than a slave—that is, as a dearly loved brother. He is especially a dearly loved brother to me. How much more can he become a brother to you, personally and spiritually in the Lord!

Philemon is unique among Paul’s letters: it is the shortest letter, it is one of only four that are addressed to individuals rather than churches, and it is the only letter that deals with a single personal matter between Paul and another Christian.

The situation.

Paul writes this letter to a “fellow worker” named Philemon, who probably lived at Colossae and became part of the church that Paul founded there. Paul is interceding on behalf of a slave of Philemon named Onesimus; Onesimus has been serving Paul’s needs while he was imprisoned and Paul says that he became Onesimus’ “father in faith.” Now, Paul is sending Onesimus back with to Philemon with this letter; Paul asks that Philemon welcome back Onesimus and that, if Onesimus owes Philemon anything, that it be charged to Paul’s account.

To my reading, Onesimus is probably a runaway slave or some other kind of indentured servant who has absconded from Philemon. It must be said, some interpreters reject the idea that Onesimus is a runaway slave (or that he is a slave at all) and suggest that Onesimus and Philemon are brothers — either spiritually or literally — who have had a falling out. I’m going to stick with my own reading here, but most of what I say here applies no matter how you read it.

Setting aside our debts.

Paul pens this letter knowing that — at least in Philemon’s eyes — Onesimus owes some kind of debt to Philemon. But, Paul says, Onesimus and Philemon are now both Christian believers, and therefore there can be nothing between them. Paul does not inquire into the nature of the debt. Paul does not get into the whys and wherefores of whether the debt between them is just or unjust. Paul simply asks that the debt be set aside, and charged to his own account.

What Paul is seeking is a re-framing of the relationship between Philemon and Onesimus. Paul pleads with Philemon by saying that Onesimus can become “more than a slave” to Philemon, he can become a “brother, personally and spiritually.” In order to do that, Philemon will have to let go of the idea that he has any right or claim to Onesimus, either as slave-holder or debt-holder.

When we read Philemon, we can’t help but think back to Paul’s other letters, where we learn that “In Christ, there is neither slave nor free.” Paul always demands unity from his churches; and Paul recognizes that unity comes at a high cost. At various times, Paul has asked his churches to set aside or give up the following things in the name of unity: distinctions between the sexes; religious and cultural identities; the benefits and comforts of wealth; class distinctions; even eating meat. Paul asks the same thing of Philemon here: for the sake of unity, Philemon should let go of whatever legal or financial hold he has over Onesimus.

Paul’s approach to Christian equality.

As a modern reader, I desperately want to read into this letter a statement from Paul condemning slavery. I would love it if we could read this letter as a blanket condemnation of that institution; but I can’t. As always, Paul is wary about making a firm statement about which practices are incompatible with Christian faith. In working to restore unity, Paul seems to prefer to take the approach that is least likely to create division or uproar. So Paul does not make a bold statement condemning slavery; instead, he intervenes in one particular case to restore the broken relationship of two men, Philemon and Onesimus.

Paul frames this request as a personal favor. I find it very touching that Paul, whom we usually find dealing with the big crises of disunity in his churches, is working to restore this relationship between two men. Throughout this series, I have made the claim that Paul cares more about cultivating unity in his churches than he does about theological propriety or engaging in grand theological discourses. This letter shows that this is true even in the individual case; Paul is willing to do whatever it takes to restore this one relationship. Paul really believes that the work of Christ in this world is to restore the things that have been broken and besmirched, and he is doing Christ’s work in this letter.

The history of interpretation.

An unfortunate consequence of Paul’s approach in this letter is that it leaves the impression that Paul is ambivalent to the issue of slavery. And, throughout history, some Christians have used the letter to Philemon as evidence that the institution of slavery is condoned by Paul and consistent with the Christian faith. Others have used it as an argument that slavery is immoral and contrary to Paul’s teachings. We have to acknowledge the fact that different interpreters will derive different meanings from the text. It is up to each of us, as active and faithful Christians, to know enough about Holy Scripture that we are able to judge whether or not a particular interpretation is valid within the broader context of the Bible.

My view is that Paul does value liberation and, if he were with us today, he would encourage the church to continue making all forms of liberation a priority. But we have to recognize that Paul places a higher value on the individual relationships that form the Body of Christ than he does on reforming society — probably because Paul knew that the early Christians had no chance at all of reforming the broader society. As present-day Christians who live in a republic where Christianity is privileged, we have to decide how to interpret scripture within our own context. May God grant us the wisdom to engage in that work.